Abstract

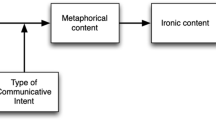

Compound figures are a rich, and under-explored area for tackling fundamental issues in philosophy of language. This paper explores new ideas about how to explain some features of such figures. We start with an observation from Stern (2000) that in ironic-metaphor, metaphor is logically prior to irony in the structure of what is communicated. Call this thesis Logical-MPT. We argue that a speech-act-based explanation of Logical-MPT is to be preferred to a content-based explanation. To create this explanation we draw on Barker’s (2004) expressivist speech-act theory, in which speech-acts build on other speech-acts to achieve the desired communicative effects. In particular, we show how Barker’s general ideas explain metaphor as an assertive-act, and irony as a ridiculing-act. We use Barker’s notion of proto-illocutionary-acts to show how metaphorical-acts and ironic-acts can build one on the other. Finally, we show that while an ironic-act can build on a metaphorical-act, a metaphorical-act cannot build on an ironic-act. This restriction on how they can be composed establishes Logical-MPT via a different route.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, metaphor embeds in a conditional’s antecedent: “If music be the food of love, then play on” (Shakespeare). Irony too embeds in a conditional’s antecedent: “If Bill has been such a fine friend, you shouldn’t speak to him again”. We discuss embedded irony in Sect. 5.

For discussion of empirical evidence supporting Temporal-MPT, see Popa (2009) and references therein. However, with a proper understanding of the speech-acts structure underlying such compounds, the psychological reality is much more complex than a sequential MPT-thesis might initially led us to believe.

Bezuidenhout adopts a widely assumed Gricean account of irony as conversational implicature—i.e. implicitly communicated content that is conveyed by means of acts of saying (or making-as-if-to-say). Ironic speakers are taken to convey some inverted content to what they say or make-as-if-to-say.

To understand Stern’s emphasis on the semantic nature of metaphor it’s useful to bear in mind these passages from his preface to Stern (2000). “I hope to show how a semantic theory can constructively inform our understanding of metaphor.” (pp. xiv), and “I am concerned primarily with one question: Given the (more or less) received conception of the form and goals of semantic theory, does metaphorical interpretation, in whole or part, fall within its scope?” (pp. xiv), and “I cannot assume … that metaphor lies within the scope of semantics … Although I shall address various objections to the semantic status of metaphor … my strongest evidence will consist in the semantic explanations I propose as working hypotheses.” (pp. xv).

“I now want to turn to a difference between them [metaphor and irony] that points to their having distinct semantic statuses” (Stern 2000: 235).

In Popa (2009: 193–201) I offer a critical evaluation of the two main arguments Stern has made in favour of his semantic view of metaphor [the “Ellipsis” argument (Stern 2006: 257–261; 70), and the “Actual Context Constraint” argument (Stern 2000: 212)]. For detailed objections, see Camp (2006), among others.

Might there be another literal meaning of ‘hot’ that can be inverted ironically and lead to the right metaphorical interpretation? The clear answer here is no. The only other recorded literal use of ‘hot’ is to mean spicy (as regarding food), the antonym for this is ‘mild’ which then simply has a second literal interpretation as ‘of mild character’, i.e. someone not disposed to strong emotion.

Wilson (2006) and Currie (2006) strongly advocate reducing the point of irony to merely expressing dissociative attitudes, say, ridiculing, mocking, disparaging attitudes towards the thought evoked by the utterance. They disagree about how this thought is evoked—say, by echoing the content of someone else’s thought/utterance, or by pretending to be someone else with a defective stance about the world. For an integrated account, see Popa-Wyatt (2014).

The ridicule or derision typically expressed with irony can also be expressed towards oneself, as when I go out in pouring rain and say to myself ‘Great!’.

The Sarc-operator is not taken by Camp to apply to all ironic utterances. She restricts the Sarc-analysis to lexical sarcasm—i.e. cases where irony targets only a word or phrase while the rest of the utterance is sincere (e.g. “Your fine friend is here”). In addition, Camp claims that irony has a multi-faceted behavior, at times contributing to truth-conditions, at other times doing something else. Here we develop the proposal for the Sarc-operator to highlight the inadequacy of content-based approaches. We do not assume that Camp is committed to such approaches.

For Camp, semanticism about irony is a natural consequence of a semanticist methodology that explains so-called ‘weak’ pragmatic intrusion into truth-conditions by postulating covert operators at the level of logical form. Parallel semantic accounts have been proposed to handle quantification (Stanley and Szabó 2000), indicative and subjunctive conditionals (King and Stanley 2005), and metaphor (Stern 2000).

Truth-aptness here is inherited from the defensive stance with respect to the state expressed. Assertions are defensive-acts; implicating-acts are not.

A proto-ironic-act is not an illocutionary-act type—an illocutionary-act type is normally produced by a self-standing ironic-act that is not tokened (see Camp and Hawthorne 2008). Camp and Hawthorne argue that sarcastic utterances prefixed with “like” have as their semantic value an illocutionary-act-type of denial. This is an interesting insight about those cases, however their notion of illocutionary-act-type does not apply to the cases discussed in this paper. Further, it remains unclear from their analysis what it is for an illocutionary-act-type to semantically express a “force/proposition complex without committing oneself to it” (2008: 13). Another idea is to say that some kind of illocutionary-act is performed but its force is cancelled (see Hanks 2007). Barker and Popa-Wyatt (2015: 6–7) argue that the cancellation-notion remains far from clear. They also show that trying to make sense of the idea of an illocutionary-act-type in terms of an indicating relation faces serious questions.

The audience must determine the range of properties P*, and here metaphor theories differ about the exact processes through which metaphorical content is derived—that is, whether P* involves weakening the denotation of literal-P, or rather transforming P-properties such that they apply to a. I’m not concerned with these issues here, but rather with the speech-act structure of metaphoric-acts.

This insight leads to a more sophisticated processing-ordering claim than a straight Temporal-MPT. I contend that knowing that the compound is primarily ironic can significantly ease metaphor processing. It does this by constraining the search to a narrower space where we look only for matching metaphorical properties that can yield in turn relevant contrasting properties. On this hypothesis, recognition of irony is prior in terms of communicative intentions, though processing-wise metaphor retains logical priority over irony.

References

Barker, S. J. (2004). Renewing meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barker, S. J., & Popa-Wyatt, M. (2015). Irony and the dogma of force and sense. Analysis, 75(1), 9–16.

Bezuidenhout, A. (2001). Metaphor and what is said: A defense of a direct expression view of metaphor. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 25, 156–186.

Brandom, R. (1983). Asserting. Noûs, 17, 637–650.

Camp, E. (2006). Contextualism, metaphor, and what is said. Mind and Language, 21(3), 280–309.

Camp, E. (2012). Sarcasm, pretence, and the semantics–pragmatics distinction. Noûs, 46, 587–634.

Camp, E., & Hawthorne, J. (2008). Sarcastic ‘like’: A case study in the interface of syntax and semantics. Philosophical Perspectives, 22, 1–21.

Carston, R. (2002). Thoughts and utterances. Oxford: Blackwell.

Currie, G. (2006). Why irony is pretence. In S. Nichols (Ed.), The architecture of the imagination (pp. 111–133). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grice, P. H. (1989). Studies in the way of words. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Hanks, P. (2007). The content-force distinction. Philosophical Studies, 134, 141–164.

King, J. C., & Stanley, J. (2005). Semantics, pragmatics, and the role of semantic content. In Z. Szabó (Ed.), Semantics vs. pragmatics (pp. 133–181). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Levinson, S. (2000). Presumptive Meanings: The Theory of Generalized Conversational Implicature. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Popa, M. (2009). Figuring the code: Pragmatic routes to the non-literal. PhD dissertation, University of Geneva.

Popa, M. (2010). Ironic metaphor: A case for metaphor’s contribution to truth-conditions. In E. Walaszewska, M. Kisielewska-Krysiuk, & A. Piskorska (Eds.), In the mind and across minds: A relevance-theoretic perspective on communication and translation (pp. 224–245). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Popa-Wyatt, M. (2014). Pretence and echo: Towards an integrated account of verbal irony. International Review of Pragmatics, 6, 127–168.

Recanati, F. (2004). Literal meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Soames, S. (2006). Understanding assertion. In J. Thompson & A. Byrne (Eds.), Content and modality: Themes from the philosophy of Robert Stalnaker (pp. 222–250). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stanley, J., & Szabó, Z. (2000). On quantifier domain restriction. Mind and Language, 15(2 and 3), 219–261.

Stern, J. (2000). Metaphor in context. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stern, J. (2011). Metaphor and minimalism. Philosophical Studies, 153, 273–298.

Wearing, C. (2013). Metaphor and the scope argument. In C. Penco & F. Domaneschi (Eds.), What is said and what is not said (pp. 141–157). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Wilson, D. (2006). The pragmatics of verbal irony: Echo or pretence? Lingua, 116, 1722–1743.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Beatriu de Pinós Project Grant No. 2013 BP-B 00266 from AGAUR/European Commission. I am very grateful for helpful discussions to Stephen Barker and Jeremy L. Wyatt. I also benefited from helpful comments on previous drafts and talks from John Barden, Delia Belleri, Liz Camp, Tyler Doggett, Ray Gibbs, Michael Glanzberg, Sam Glucksberg, Peter Pagin, Philip Percival, Ken Walton, and two anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Popa-Wyatt, M. Compound figures: priority and speech-act structure. Philos Stud 174, 141–161 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0629-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0629-z