- Submit

-

Browse

- All Categories

- Metaphysics and Epistemology

- Value Theory

- Science, Logic, and Mathematics

- Science, Logic, and Mathematics

- Logic and Philosophy of Logic

- Philosophy of Biology

- Philosophy of Cognitive Science

- Philosophy of Computing and Information

- Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Physical Science

- Philosophy of Social Science

- Philosophy of Probability

- General Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Science, Misc

- History of Western Philosophy

- Philosophical Traditions

- Philosophy, Misc

- Other Academic Areas

- More

Sonic Booms in Blanchot

Angelaki 23 (3):144-157 (2018)

Abstract

Blanchot’s rejection of vision as the fundamental philosophical metaphor is well known: “Seeing is not speaking” (The Infinite Conversation (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1993) 25). Furthermore, his central idea of the limit-experience (borrowed from Bataille) is a “detour from everything visible and invisible” (210). As part of his Heideggerian heritage, the increased importance of hearing (and aurality in general) lacks the critical appraisal it deserves. Pari passu for voice. Blanchot’s investigation of voice, spoken, interior, literary, is extensive. Various works of fiction, notably The One Who Was Standing Apart From Me, explore the meme, which is intensified in critical essays on Hölderlin, Kafka, Rilke, and Valéry, where the voice’s musicality is given to performance. The studies exemplify the operation of “pure voice,” voice no longer in relation to and under the constraints of the interlocutor: its rhythm, tempo, and melody. His clearest, though lapidary, remarks on voice appear in discussion of the Narcissus mythomeme. There, voice is related not only to Narcissus’ love of an (unrecognized) self but also to the intrigue of Echo and her mimetic reproduction of voice. I give a close reading of Blanchot’s rendition of Ovid’s story to show the central role that voice plays in his “great refusal” of philosophy and concomitant opening to the outside, the “beyond being,” its nomadism and messianism.Author's Profile

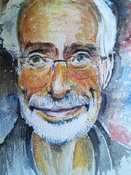

David Appelbaum

State University of New York (SUNY)

Analytics

Added to PP

2018-06-01

Downloads

452 (#64,879)

6 months

90 (#77,419)

2018-06-01

Downloads

452 (#64,879)

6 months

90 (#77,419)

Historical graph of downloads since first upload

This graph includes both downloads from PhilArchive and clicks on external links on PhilPapers.

How can I increase my downloads?