- Submit

-

Browse

- All Categories

- Metaphysics and Epistemology

- Value Theory

- Science, Logic, and Mathematics

- Science, Logic, and Mathematics

- Logic and Philosophy of Logic

- Philosophy of Biology

- Philosophy of Cognitive Science

- Philosophy of Computing and Information

- Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Physical Science

- Philosophy of Social Science

- Philosophy of Probability

- General Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Science, Misc

- History of Western Philosophy

- Philosophical Traditions

- Philosophy, Misc

- Other Academic Areas

- More

The Zygote Argument Is Still Invalid: So What?

Philosophia 49 (2):705-722 (2020)

Abstract

In this essay, I explain why Gabriel De Marco's attempts to "solve" the invalidity problem for the Zygote Argument were non-starters. The first solution he describes was originally developed by Mickelson (2012/2015) and already adopted by Mele (2013), but De Marco presents it as his own using an idiosyncratic labelling system. [[In recent work, De Marco has abandoned the tripartite taxonomy on which "compatibilism is false" and "incompatibilism is true" name different doctrines. Following Mele 2013, De Marco now uses the revisionary definition of 'incompatibilism' on which this term refers to mere incompossibilism; he provides *no name at all* for the explanatory thesis that he formerly called incompatibilism (following standard practice and the original meaning of the term). Given that De Marco's revisionary labelling strategy was the only novel component of his first "solution", it seems that even De Marco doesn't want to use his idiosyncratic labelling strategy -- presumably because the strategy isn't viable (see De Marco, Gabriel & Cyr, Taylor W. (2024). Manipulation Cases in Free Will and Moral Responsibility, Part 1: Cases and Arguments. Philosophy Compass 19 (12):e70009.]] De Marco's second response fails because it is grounded in a patently invalid argument. Most importantly, De Marco (like Mele before him) fails to even mention that Mickelson wasn't interested in the Zygote Argument per se, nor did she have the quixotic aim of providing "correct" definitions of anachronistic jargon like 'compatibilism' and 'incompatibilism' (for reasons explained in Mickelson's 2015 critique of Vihvelin's three-fold classification). Mickelson's invalidity objection served to highlight several novel and dialectically significant lessons, such as: it is surprisingly difficult to close the "explanatory gap" between incompossibilism and the standard causal-factors (causal luck) explanation for incompossibilism. Historically, this gap has been closed with question-begging assumptions (e.g. free is an ability to do otherwise) and invalid reasoning (e.g. the original Zygote Argument). Pereboom is one of the only philosophers to confront the challenge of closing this gap directly, but the best-explanation reasoning he uses to close the gap is incomplete and arguably incorrect (Mickelson, "The Problem of Free Will and Determinism: An Abductive Approach" and "Hard Times for Incompatibilism"). Indeed, there appears to be no argument in the free-will literature which closes this gap in a philosophically acceptable way. Quite literally, there appears to be NO logically viable, non-question-begging argument for the "incompatibilist" view that deterministic causal factors undermine (vitiate, destroy, are antagonistic to) free will in the history of the free-will literature as a whole! Unfortunately, some philosophers prefer to focus on the definitions of jargon and don't want to "fuss" over fundamental philosophical errors and oversights--and no one else should fuss over such things either. This paper was written for fussier philosophers who are attracted to the idea of exploring the new avenues of research that have opened up by exposing the explanatory gap between incompossibilism and rival explanations for the truth of incompossibilism. [] *My thanks to the referees and editors at Philosophia for publishing this corrective when Phil Studies would not. []Author's Profile

Kristin M. Mickelson

University of Colorado, Boulder

Analytics

Added to PP

2018-08-03

Downloads

665 (#43,728)

6 months

239 (#13,248)

2018-08-03

Downloads

665 (#43,728)

6 months

239 (#13,248)

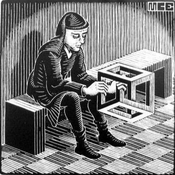

Historical graph of downloads since first upload

This graph includes both downloads from PhilArchive and clicks on external links on PhilPapers.

How can I increase my downloads?